Why Does Money Fail? Part 2

Electronic money is showing its fatal flaws

Welcome to Issue 3 of New Money Matters.

In January, many of us start to think about savings goals and financial matters.

So, the end of the year is a good time to assess the state of our money (2024 was a pretty big year for me).

I’ll be looking ahead to where money is headed in 2025. But first, Part 2 of my examination of why money fails.

In Part 1, we saw how three types of money failed.

Gold was too challenging to verify, store, and divide.

Coins were degraded through coin clipping, leading to inflation. They were also too heavy to transport.

Paper was more transportable but could still not be used globally. Bookkeeping and records were also not instant and trustworthy.

These types of money were eventually replaced by a new contender, electronic money.

“Electronic money is a payment instrument whereby monetary value is electronically stored on a technical device in the possession of the customer. The amount of stored monetary value is decreased or increased, as appropriate, whenever the owner of the device uses it to make a purchase, sale, loading or unloading transaction.” Definition according to the European Central Bank.

There are a few important distinctions to make when discussing electronic money.

I consider electronic money to be any transfer of value conducted remotely in a non-physical form.

While fiat currency is not directly linked to electronic means, the failure of electronic money is intrinsically linked to the problems with fiat currency.

A Brief History of Electronic Money

We may think of PayPal addresses, online banking, or zapping sats when we say ‘electronic money. The truth is that the technology goes back to the 19th century. Western Union debuted its electronic funds transfer (wire transfer) in 1870 via the copper wires of the telegraph network.

In 1910, the Federal Reserve first used the telegraph to transfer money, and by the 1950s, cash payments began to decrease in favour of deferring payments and accumulating debt. This was made possible by the instant transactions of credit cards like American Express (introduced in the 1950s).

The Automated Clearing House (ACH) was officially established in 1972, and SWIFT (The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) facilitated cross-border payments when it went live in 1977.

The advent and spread of the Internet in the 1990s ramped up innovation. Electronic payments evolved at light speed, with online banking platforms, contactless payments, digital wallets, and more ways to move money electronically emerging.

So, with all this innovation and convenience, what went wrong?

Signs of failure

You’re probably reading this thinking, ‘Electronic money hasn’t failed. My Visa, ApplePay, and online bank work fine for me.’

That may be true, but it’s not the case globally. The challenges are becoming apparent.

Electronic money is not equal access

As the West forges ahead with technological innovation, faster money, and quicker settlement, the developing world gets left behind. Bigger conglomerates like Stripe and Paypal operate from the US and Europe, processing international payments.

Yet merchants in countries excluded from those programs have no means to collect payment for digital products or services. The Internet offers an opportunity to all, but those who benefit most have the most up-to-date hardware and access to certain processors.

If 1.4 billion adults have no access to a bank account, how many more lack access to PoS terminals, NFC payment chips, credit cards and payment platforms?

As technology gathers pace at an exponential rate, residents outside of G20 countries fall further behind in terms of being able to process payments quickly.

Currency competition and manipulation

There are 180 competing fiat currencies currently circulating.

Put simply, local governments want to protect their own currency, often blocking citizens from transacting electronically in more stable currencies like the Euro or the US Dollar. Again, this impacts those in lower-performing economies worse.

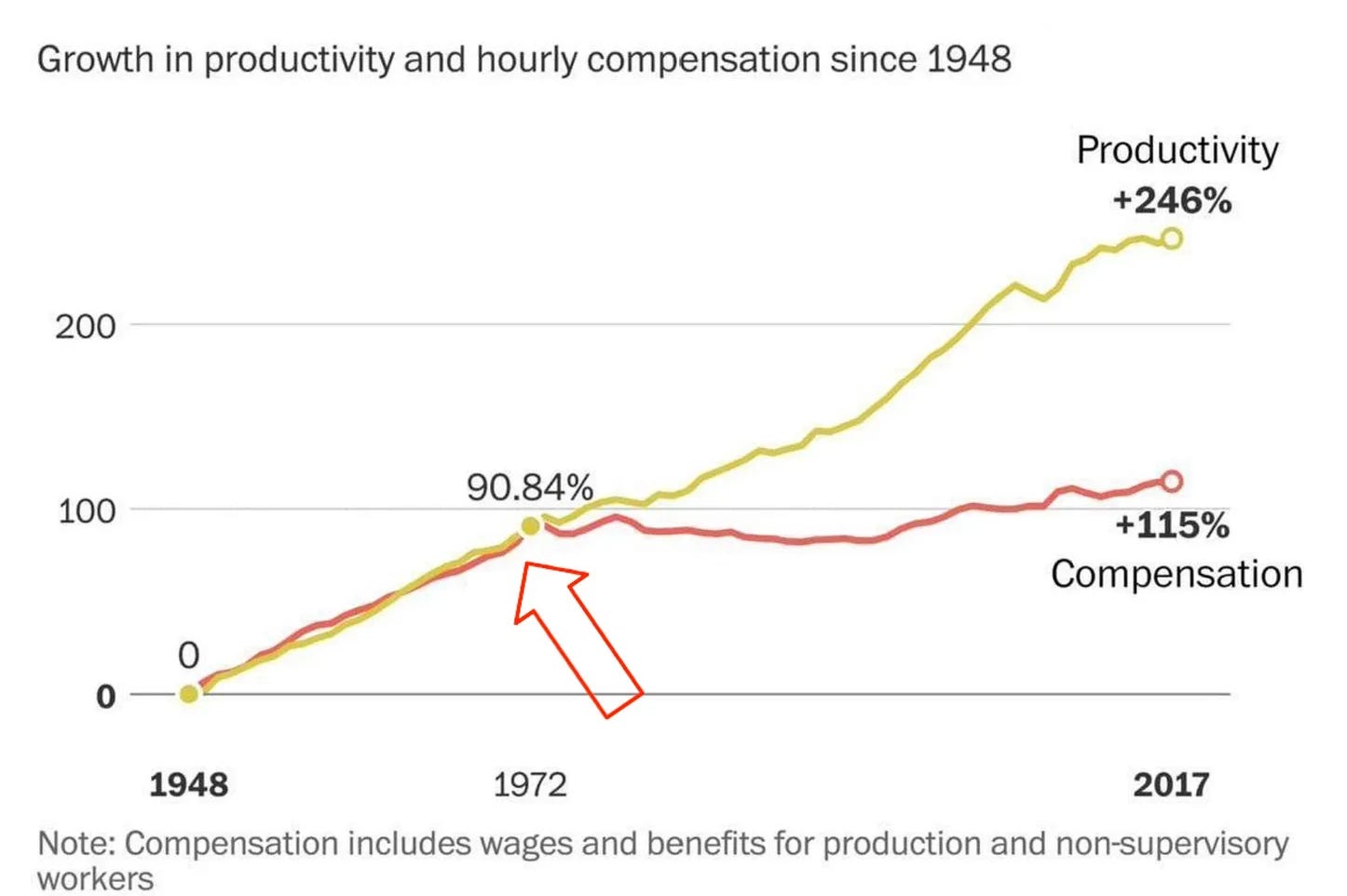

When all government-issued currencies were officially decoupled from the Gold Standard in 1971, electronic money facilitated rapid inflation.

The strength of electronic money (its lack of physical presence) is also its weakness. As governments digitally print more money by issuing debt, citizens’ money loses value rapidly.

And even though productivity has rocketed due to technological advances in this period, those gains have not been passed on to workers.

My position is that the lack of understanding of our complex electronic fiat monetary system has led to those in charge of the money printer benefitting most.

Risk of third-party failures

The electronic money we use is not peer-to-peer (like cash). It involves several intermediaries. This brings risk and cost to the consumer.

Western Union is an example of a legacy ‘middleman’ company that charges high commissions to provide remittance and transfer services to countries that are poorly adapted for electronic money. Consumers have little power to seek alternatives. Competitors have little ability to challenge the hegemony of the powerful conglomerate. Although Western Union has a history and trusted brand reputation, customers would not be protected if the institution failed.

Until electronic cash can cut out the middleman, customers will not be able to trust the process. They will also have to keep paying handsomely for this inefficient process.

Governmental overreach and privacy concerns

Electronic providers like PayPal can switch off a customer’s ability to use their service. This could be done for any reason, as PayPal is a private company. If a customer’s views or activity are considered undesirable (not illegal), the private company may wish to err on the side of caution. They don’t want to lose licenses or come under scrutiny from local governments. So customers are ‘unbanked’.

In this way, users are never in control of their money. Transactions depend on compliance with a host of societal, political, and economic norms.

Governments that implement Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) can take this compliance several steps further. The de-privatization of electronic money would allow complete transactional transparency and records of all monetary movements. Money could be inflated without control, programmed to expire, limited or restricted for certain purchases, or expunged.

CDBCs may increase monetary efficiency by removing the middleman, but they pose other, greater dangers.

Looking ahead

We are heading in the direction of multiple forms of money. We mustn’t put all our eggs in one basket. The future will likely include several types of money included in the image above. Electronic (third-party facilitated) money is not dead yet. However, we must continue to seek solutions to ensure money becomes more efficient, sound, equitable, and beneficial for all.

Thanks for reading this issue. Please feel free to add your thoughts and comments!

A couple of final points:

Check out my 2025 predictions for bitcoin (and add your own in the comments).

One of our advisors at Bringin, Joe Bryan, is getting ready to launch a major project that explains societal and monetary problems. The best part is that we already have the solution. Keep following Joe for more info.